- Home

- Wyomia Tyus

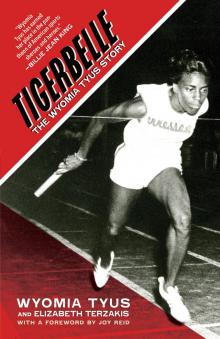

Tigerbelle

Tigerbelle Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Foreword by Joy Reid

Introduction

Chapter 1. Suster: Walking the Farm

Chapter 2. “You Just Ran Yourself into Some Shoes . . .”

Chapter 3. “Now Run Yourself into a Tigerbelle T-shirt!”

Chapter 4. First Gold, New Growth: The 1964 Olympics

Chapter 5. College As Usual

Chapter 6. Spiders and Fires and Bombs

Chapter 7. B2B100m

Chapter 8. After the Deluge

Chapter 9. Another Life to Live

Chapter 10. Making a Way

Chapter 11. Getting Out of the Blocks (Like Everybody Else)

Chapter 12. Mr. Temple’s Legacy

Chapter 13. Black Women in Sports: Then and Now

Chapter 14. Blacks Lives Have Always Mattered

Appendix. The Tigerbelles

Endnotes

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Copyright & Credits

About Akashic Books

To my parents, Willie and Marie, for the great

foundation, wisdom, and encouragement you gave me. You are loved and missed.

To Mr. Temple, my father figure, my educator,

and my friend. It is because of you that I am saying more than four words now. I just wish that this story could have been told sooner so that you could smell the flowers.

To my brothers: You always said you taught me

everything I know, and you did. And for that,

I am grateful. Thank you for making sure I got to play and for making sure I always stayed in the fight.

—W.T.

Foreword by Joy Reid

I was not yet born when Tommie Smith and John Carlos turned the 1968 Summer Olympic Games upside down with their fist-in-the-air protest (though I would come along not too long after). But growing up, that year’s Games loomed large in the Black Pride origin story in our house, as dictated by my five-foot-three Guyanese spitfire of a mother. In our house, the Olympics was a time to gather around the family TV set, cheer on Black Excellence, and laugh in the face of supposed Black shame. We were achievers, not victims or merely “descendants of slaves.” Every gold medal was a badge of honor we somehow pieced out among all of us. Say it loud: I’m Black and I’m proud!

For me—a skinny, bespectacled, nerdy kid who was nonetheless athletic, who could dribble a basketball like a boy, jump my Schwinn bike like a BMX, and sprint the 100, the 200, and the anchor leg of the 4x400 relay faster than the lithe, light-skinned, perfectly ponytailed girls in my mostly Black Denver suburb—seeing the Olympic runners, particularly the Black women who are so often not recognized as part of the sports world, was revelatory.

But even those of us who pride ourselves on knowing history often know almost nothing. We learn how much “nothing” we know with every new tale of triumph and overcoming that falls into our laps like a lucky coin.

The story of Wyomia Tyus is such a coin. For decades, it sat on a shelf, suspended above but never able to fill a blank space in my memory as I searched for more Black girl role models and found almost none to crowd out my male idols: Arthur Ashe and Muhammad Ali. Until there were the Williams sisters, Venus and Serena, “sporty” Black girls were an aberration, not the norm. Black women sports heroes were distilled down to a single name: Wilma Rudolph—a Black woman and a sprinter, but, as it turns out, not the only Black female sprinter to make an indelible (if for far too long invisible) mark on the world sporting stage.

Wyomia earned her place in the pantheon of American athletic greatness by doing something that no one—man or woman—had ever done before. Her story—growing up on a remote farm in rural Georgia and emerging onto the Olympic stage in 1964 and 1968 as one of the most decorated runners ever to don cleats—is one that every Black girl, every athlete, and every American should know. Hers is the legend we have never discussed. It was not until the second decade of the twenty-first century that America learned a small piece of the hidden history of Black women in the 1960s through the movie Hidden Figures. Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story is the Hidden Figures of Olympic legend. Her athletic ability as well as her politics and her grace demand that we fight for her to be remembered so that we can not only revel in her accomplishments but also learn from them as a new generation of Black women leads the struggles of tomorrow both on and off the field of play.

Like most of the Black women who toiled in the trenches of the Civil Rights Movement in anonymity, Wyomia has yet to have her tale told on a scale equal to its magnitude. Now, we can hear it in her own voice. And in that voice we hear the distinct cadence of America’s racial and gender history.

Joy Reid is the host of MSNBC’s AM Joy. She is also the author of the book Fracture: Barack Obama, the Clintons, and the Racial Divide.

Introduction

If you want to get to know Wyomia[1] Tyus, there are two videos you should watch.[2] The first, in black-and-white, shows Tyus winning the 100-meter dash at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City and becoming the first person—not the first woman, the first person—ever to win gold medals in the 100 at two consecutive Olympic Games. First in real time, then in slow motion, Tyus bursts from the blocks, establishes a lead, and leans over the finish line eleven seconds later. After the slow-motion run-through of the race, the film cuts to Tyus on the medal stand, graciously shaking hands with bronze medalist Irena Szewińska and drawing the attention of teammate and silver medalist Barbara Ferrell to Szewińska’s proffered hand. It is raining; all three women are dripping wet, but Tyus is laughing, shaking the rain from her fingers, maybe even dancing a little. She appears to be in a state of grace.

The second video also revolves around the women’s 100-meter final at the 1968 Olympics. Although Tyus is not the primary subject of the film, she becomes the focus of attention as soon as the main contenders are introduced. A beatific grin on her face, Tyus again seems to be dancing. A voice-over by Olympic medalist Dwight Stones describes Tyus as “a natural-born sprinter” and notes “the psychological strength that she would bring to a race.” According to Stones, “She would just intimidate you out of any chance of beating her. And she really wasn’t like that; she was actually kind of shy. But on the track, she was an assassin.”

Tyus is shown in a preliminary heat, running, winning, smiling, waving to someone in the crowd. Then the footage jumps to the runners preparing to get into their blocks, and it becomes clear that Tyus actually was dancing: “She’s standing there, and everybody else’s faces are very nervous. At the beginning of a final, at the Olympics, of course you’re nervous on some level—good nervous, maybe bad nervous—Tyus maybe even was nervous too,” Stones admits. “But the way she chose to manifest it was that she got there by her starting block and she started doing the ‘Tighten Up’—and what that did was it loosened her up and tightened everybody else up—and that’s why she did it. It was just another technique, it was another thing that she thought of that she had never done, that they had never seen, that was going to take everyone else out of their game.”

As Tyus dances the “Tighten Up,” which she described to me as a “herky-jerky sort of dance” popularized by Archie Bell & the Drells, the camera pans the stands, where Black men—Jamaicans, according to Tyus—with rhythm sticks and hand drums of all sizes play an accompaniment. And then Tyus runs, and wins, and makes history. Twenty years would pass before Tyus’s feat was equaled, and close to fifty before it was surpassed. Only four other runners have ever done what she did.

* * *

Wyomia Tyus—natural-born sprinter, shy assassin, and joyful dancer—is a sports legend and one of the Olympic giants of the twentieth century. Tyus won her first Olympic gold in the 100 at the 1

964 Games in Tokyo, Japan, where she matched Wilma Rudolph’s world record and helped her team to win silver in the 4x100 relay. In 1968, Tyus not only became the first person to win back-to-back gold medals in the 100 but also set a new world record for the event and racked up another gold in the 4x100 relay. In the years between the two Olympics, Tyus took the outdoor 100-meter Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championship in 1965 and 1966, won the 220-yard dash in 1966, and, in indoor competition, won the 60-meter dash and set new world records in 1965, 1966, and 1967. Tyus is unfailingly modest about these accomplishments: “I don’t focus on my records,” she confesses. “Time never broke a tape.”

Tyus’s groundbreaking Olympic victory in 1968 occurred amid the political tumult of that era. The success of the Tet Offensive in January of 1968 increased domestic opposition to the American war in Vietnam while the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April precipitated a radicalization in the fight for racial justice. Student protests were on the rise the world over, in Western and Eastern Europe, in South America and Asia, and in Mexico as well as the United States. Ten days before the Games began in Mexico City, students protesting police violence were massacred by government troops in Tlatelolco’s Plaza de las Tres Culturas as part of the country’s efforts to make the city “presentable” for Olympic visitors.[3]

As a Black woman from the Jim Crow South and a participant in the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), Tyus was acutely aware of the existence of injustice not just in the US but around the world. She also understood the significance of Black athletes in the context of the Cold War and in light of the United States’ self-proclaimed preeminence as an exemplar of democratic and individual rights: the Olympics made America vulnerable to exposure by providing Black athletes—including those who had grown up drinking from segregated water fountains and knew firsthand about urban blight—the opportunity to stand on a world stage. With this in mind, Tyus dedicated her gold medal in the 4x100 relay to Olympic protestors Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who shocked the upper echelons of the Olympic world and thrilled activists everywhere by raising their black-gloved fists on the medal stand to protest human rights violations at home and abroad. By throwing her support behind them, Tyus played a significant—if underrecognized—part in bringing the movement for human rights into the arena of international athletic competition.

For Tyus, the movement was all about inclusion: “We are all in this together. That’s what the whole human rights project has always been about. And that’s what I said to the reporters. But none of that got printed, of course.”

It is also significant that Tyus demonstrated her solidarity despite the fact that the leaders of the OPHR—including Smith and Carlos—did not include her or other Black female athletes in their organizing. Talking about it, Tyus is neither bitter nor resentful: “Everyone wants to be wanted and needed and feel like they’re a part. And that wasn’t there for us. I’m not upset with them. It’s just more that, ‘How could you not think of us?’”

She holds true to the principles of inclusion and solidarity and has no regrets—even when it is suggested that her support for Smith and Carlos might explain the fact that her first-in-the-world accomplishment has gone largely unnoticed.

“It’s either that,” she says, “or the fact that I’m a Black woman.” When asked if she considered the possible consequences of her action, she notes that she did, but, at the time, she didn’t really care: “At that point, I knew that I was going to be me, and whatever else was going to happen was going to happen.”

* * *

Tyus came to the Games as one of Tennessee State University’s Tigerbelles, a women’s track-and-field program that in its heyday produced forty Olympic athletes and twenty-three medalists. As a key protagonist in the triumphant tale of the Tigerbelles, Tyus provides a window into a remarkable—and remarkably overlooked—story. She accurately describes her coach, Ed Temple, who passed away in September of 2016, as a visionary: Temple led the program for forty-four years and was able to imagine a place for women in sports decades before the enactment of Title IX.

Like Mr. Temple, Tyus’s parents had a vision: that their children should be children and not have to shoulder the responsibilities of adulthood until they were grown. In talking about her early life, Tyus describes the farm where her father worked and her family lived as a “safe haven” from the racism of the era—despite the fact that the Klan was a regular participant in local parades. She attributes some portion of her early athleticism to the fact that she played with, competed against, and often beat both her brothers and the male children of her neighbors, who were all white. Tyus had to—got to—play with the boys because the white girls “were never allowed to play with us—definitely not with Black boys, and not with me either. But that was okay with me. They didn’t do too much playing anyway.” The most athletic thing the white girls were allowed to do was ride horses, but even then, Tyus says, they had to be “prim and proper.”

Tyus’s parents would maintain their safe haven until Tyus turned fourteen and a family tragedy changed their lives forever. In the wake of her family’s misfortune, Tyus began competing in track, primarily as a means to keep “busy” and “stay out of trouble.” She was fifteen and running at her first state meet in Fort Valley, Georgia, when she was scouted by Ed Temple. Not long after, Tyus would take her first train ride to Temple’s summer clinic at Tennessee State in Nashville. Following Temple’s strict regimen of intense workouts, academic dedication, and mutual support, Tyus and her teammates, all young Black women, navigated the sea of racism and sexism that was the Jim Crow South and 1960s America to become world-class scholar-athletes and, in many cases, lifelong friends. Thrice-daily practices developed Tyus’s speed and stamina while the generosity and guidance of “older” runners like the legendary Wilma Rudolph and Edith McGuire helped her to make her way both as an athlete and as a student. Mr. Temple insisted that the Tigerbelles earn their degrees and acquire skills to live on once their competitive careers were over, and this insistence—along with her own steely will and abundant raw talent—contributed greatly to Tyus’s success both on and off the track. It also led to a 99 percent graduation rate for the Tigerbelles at a time when only a tiny fraction of American women—let alone American Black women—were able to earn four-year degrees.

* * *

The arc of Tyus’s life—from her childhood as the daughter of a tenant dairy farmer in Griffin, Georgia, to her retirement as a naturalist in Los Angeles, California—would be worth following even if she had never medaled at the Olympics. Yet, as is the case with so many Black women of her day, her story has gone untold, her achievements unsung. One explanation for this is the fact that her ascent to Olympic glory occurred at a time when the editors at Sports Illustrated were less interested in covering the Black female athletes who would actually represent the United States in the Olympic Games than they were in promoting a white Texas coach nicknamed “Flamin’ Mamie” and her all-white Bouffant Belles. The cover of SI’s April 20, 1964, issue features three heavily made-up and precipitously coiffed white women with the patronizing caption: “Texas Girls Aim for Tokyo.”[4]

A breathtaking testament to the interlocking powers of racism and sexism, the article effortlessly erases the accomplishments of Black female athletes while simultaneously mocking the aspirations of white female athletes. Meanwhile, the story of Wyomia Tyus and her teammate Edith McGuire—who had been born in the same state, experienced similar family tragedies, and went to the same university—went unreported. McGuire was favored to take the gold in the 100 in 1964, making Tyus’s eventual win a stunning upset and their uninterrupted friendship of considerable human interest—but where’s the story in that?

It would be nice to think that the world has changed a lot since then, and progress has indeed been made—much of it thanks to the efforts of athletes like Tyus, who together with Billie Jean King and other female sports superstars formed the Women’s Sports Foundation to promote the

participation and publicity of women in sports. But there is still a long way to go, and the problem is not a lack of exceptional female athletes but a combination of structural barriers and widely broadcast individual bigotry. In March of 2016, tennis tournament director Raymond Moore made headlines by presenting his opinion that the Women’s Tennis Association “rides on the coattails of men” and that, “lady player[s]” should go down on their “knees every night and thank God” for the male players who have “carried the sport.” In making this statement, Moore demonstrated not only misogyny but ignorance: female stars like Venus and Serena Williams have been the face of tennis for the last twenty years, and the women’s finals of the last two US Opens had higher television ratings than the men’s. Despite this, female players still make less than male players overall, and their matches are all too often relegated to midafternoon while the men’s matches occupy prime time.[5]

Women’s sporting successes go unrecognized in other arenas as well. Sexism in the coverage of the 2016 Summer Olympic Games was a story in itself.[6] “Highlights” included Michael Phelps’s tie for silver taking precedence over Katie Ledecky’s world record–annihilating (by 11.83 seconds!) gold in a headline, and a marriage proposal being called “an even bigger prize” than Chinese diver He Li’s silver medal.[7]

Racism, as usual, was also in play, for example, in the form of a photograph of gymnast Simone Biles misidentified in a column about gymnast Gabby Douglas.[8] When it comes to more permanent and in-depth coverage, the pattern repeats: of Amazon’s first twenty “Hot New Releases” in sports biographies of 2017,[9] only two are by or about women—Caitlyn Jenner’s The Secrets of My Life and Women in Sports: 50 Fearless Athletes Who Played to Win, which features one page of whimsical illustration and one page of biographical information apiece for fifty pioneering female athletes. And while stories of female athletes in general are difficult to find, the experience of Black women athletes in particular has been neglected by sportswriters and sports historians for as long as women have competed, much to the detriment of each successive generation of Black female athletes.

Tigerbelle

Tigerbelle